Reproducible Research Badges

12 Sep 2017 | By Lukas Lohoff, Daniel NüstThis blog post presents work based on the study project Badges for computational geoscience containers at ifgi. We thank the project team for their valuable contributions!

Nüst, Daniel, Lukas Lohoff, Lasse Einfeldt, Nimrod Gavish, Marlena Götza, Shahzeib T. Jaswal, Salman Khalid, et al. 2019. “Guerrilla Badges for Reproducible Geospatial Data Science (AGILE 2019 Short Paper).” EarthArXiv. June 19. doi:10.31223/osf.io/xtsqh.

Introduction

Today badges are widely used in open source software repositories. They have a high recognition value and consequently provide an easy and efficient way to convey up-to-date metadata. Version numbers, download counts, test coverage or container image size are just a few examples. The website Shields.io provides many types of such badges. It also has an API to generate custom ones.

Now imagine similar badges, i.e. succinct, up-to-date information, not for software projects but for modern research publications. It answers questions such as:

- When was a research paper published?

- Is the paper openly accessible?

- Was the paper published in a peer reviewed journal?

- What is the research’s area of interest?

- Are the results reproducible?

These questions cover basic information for publications (date, open access, peer review) but also advanced concepts: the research location describes the location a study is focusing on. A publication with reproducible results contains a computation or analysis and the means to rerun it - ideally getting the same results again.

We developed a back-end service providing badges for reproducible research papers.

Overview of badges for research

We are however not the first nor the only ones to do this: ScienceOpen is a search engine for scientific publications. It has badges for open access publications, content type, views, comments and the Altmetric score as displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: ScienceOpen badges in a search result listing.

These are helpful when using the ScienceOpen website, but they are not available for other websites. Additional issues are the inconsistent style and missing information relevant for reproducible geosciences, e.g. reproducibility status or the research location.

Badges are also used directly on publications, without the search portal “middleman”. The published document, poster or presentation contains a badge along with the information needed to access the data or code. The Center for Open Science designed badges for acknowledging open practices in scientific articles accompanied by guidelines for incorporating them into journals’ peer review workflows and adding them to published documents, including large colored and small black-and-white variants. The badges are for Open Data, Open Materials, and Preregistration of studies (see Figure 2) and are adopted by over a dozen of journals to date (cf. Adoptions and Endorsements).

Figure 2: COS badges.

University of Washington’s eScience Institute created a peer-review process for open data and open materials badges https://github.com/uwescience-open-badges/about based on the COS badges. The service is meant for faculty members and students at the University of Washington, but external researchers can also apply. The initiative also has a list of relevant publications on the topic.

A study by Kidwell et al. [1] demonstrates a positive effect by the introduction of open data badges in the journal Psychological Science: After the journal started awarding badges for open data, more articles stating open data availability actually published data (cf. [2]). They see badges as a simple yet effective way to promote data publishing. The argument is very well summarized in the tweet below:

Simple rewards are sufficient to see the change we want to occur #SSP2017 pic.twitter.com/P1H4hpQeqN

— David Mellor (@EvoMellor) 1. Juni 2017

Peng [3, 4] reports on the efforts the journal Biostatistics is taking to promote reproducible research, including a set of “kite marks”, which can easily be seen as minimalistic yet effective badges. D and C if data respectively code is provided, and R if results were successfully reproduced during the review process (implying D and C). Figure 3 shows the usage of R on an article’s title page (cf. [5]).

Figure 3: Biostatistics kite mark R rendering in the PDF version of the paper.

The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) provides a common terminology and standards for artifact review processes for its conferences and journals, see their policies website section on Artifact Review Badging. The have a system of three badges with several levels accompanied by specific criteria. They can be independently awarded:

- Artifacts Evaluated means artifacts were made available to reviewers and awarded the level Functional or Reusable

- Artifacts Available means a deposition in a repository ensures permanent and open availability (no evaluation)

- Results Validated means a third party successfully obtained the same results as the author at the levels Results Replicated (using, in part, artifacts provided by the author) or Results Reproduced (without author-supplied artifacts)

Figure 4 shows a rendering of the ACM badges.

Figure 4: ACM badges, from left to right: Artifacts Evaluated – Functional, Artifacts Evaluated – Reusable, Artifacts Available, Results Replicated, and Results Reproduced. (Copyright © 2017, ACM, Inc)

Although these examples are limited to a specific journal, publisher, or institution, they show the potential of badges. They also show the diversity, limitations, and challenges in describing and awarding these badges.

For this reason, our goal is to explore sophisticated and novel badge types (concerning an article’s reproducibility, research location, etc.) and to find out how to provide them independently from a specific journal, conference, or website.

An independent API for research badges

Advanced badges to answer the above questions are useful for literature research, because they open new ways of exploring research by allowing to quickly judge the relevance of a publication, and they can motivate efforts towards openness and reproducibility. Three questions remain: How can the required data for the badges be found, ideally automatically? How can the information be communicated? How can it be integrated across independent, even competitive, websites?

Some questions on the data, such as the publication date, the peer review status and the open access status can already be answered by online research library APIs, for example those provided by Crossref or DOAJ. The o2r API can answer the remaining questions about reproducibility and location: Knowing if a publication is reproducible is a core part of the o2r project. Furthermore, the location on which a research paper focuses can be extracted from spatial files published with an Executable Research Compendium [6]. The metadata extraction tool o2r-meta provides the latter feature, while the ERC specification and o2r-muncher micro service enable the former.

How can we integrate data from these different sources?

o2r-badger is a Node.js application based on the Express web application framework. It provides an API endpoint to serve badges for reproducible research integrating multiple online services into informative badges on scientific publications. Its RESTful API has routes for five different badge types:

- executable: Information about executability and reproducibility of a publication

- licence: licensing information

- spatial: a publication’s area of interest

- releasetime: publication date

- peerreview: if and by which process the publication was peer reviewed

The API can be queried with URLs following the pattern /api/1.0/badge/:type/:doi. :type is one of the aforementioned types, and :doi is a publication’s Digital object identifier (DOI).

The badger currently provides badges using two methods: internally created SVG-based badges, and redirects to shields.io. The redirects construct a simple shields.io URL. The SVG-based badges are called extended badges and contain more detailed information: the extended license badge for example has three categories (code, data and text, see Figure 5), which are aggregated to single values (open, partially open, mostly open, closed) for the shields.io badge (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: An extended licence badge reporting open data, text and code.

Extended badges are meant for websites or print publications of a single publication, e.g. an article’s title page. They can be resized and alternatively provided pre-rendered as a PNG image. In contrast, the standard shields.io badges are smaller, text based badges. They still communicate the most important piece of information:

Figure 6: An shields.io based small badge, based on the URL https://img.shields.io/badge/licence-open-44cc11.svg.

They excel at applications where space is important, for example search engines listing many research articles. They are generated on the fly when a URL is requested (e.g. https://img.shields.io/badge/licence-open-44cc11.svg) which specifies the text (e.g. licence and open) and the color (44cc11 is a HTML color code for green).

Let’s look at another example of an executable badge and how it is created.

The badge below is requested from the badger demo instance on the o2r server by providing the DOI of the publication for the :doi element in the above routes:

https://o2r.uni-muenster.de/api/1.0/badge/executable/10.1126%2Fscience.1092666

This URL requests a badge for the reproducibility status of the paper “Global Air Quality and Pollution” from Science magazine identified by the DOI 10.1126/science.1092666. When the request is sent, the following steps happen in o2r-badger:

- The badger tries to find a reproducible research paper (called Executable Research Compendium (ERC) via the o2r API. Internally this searches the database for ERC connected to the given DOI.

- If if finds an ERC, it looks for a matching job, a report of a reproduction analysis.

- Depending on the reproduction result (

success,running, orfailure) specified in the job, the badger generates a green, yellow or red badge. The badge also contains text indicating the reproducibility of the specified research publication. - The request is redirected to a shields.io URL link containing the color and textual information..

The returned image contains the requested information, which is in this case a successful reproduction:

URL: https://img.shields.io/badge/executable-yes-44cc11.svg

Badge:

If an extended badge is requested, the badger itself generates an SVG graphic instead.

Badges for reproducibility, peer review status and license are color coded to provide visual aids. They indicate for example (un)successful reproduction, a public peer review process, or different levels of open licenses. These badges get their information from their respective external sources: the information for peer review badges is requested from the external service DOAJ, a community-based website for open access publications. The Crossref API provides the dates for the releasetime badges. The spatial badge also uses the o2r services. The badger service converts the spatial information provided as coordinates into textual information, i.e. place names, using the Geonames API.

Spread badges over the web

There is a great badge server, and databases providing manifold badge information, but how to get them displayed online? The sustainable way would be for research website operators to agree on a common badge system and design, and then incorporate these badges on their platforms. But we know it is unrealistic this ever happens. So instead of waiting, or instead of engaging in a lengthy discourse with all stakeholders, we decided to create a Chrome extension and augment common research websites. The o2r-extender automatically inserts badges into search results or publication pages using client-side browser scripting. It is available in the Chrome Web Store and ready to be tried out.

The extender currently supports the following research websites:

- Google Scholar https://scholar.google.de/

- DOAJ.org https://doaj.org/

- ScienceDirect.com http://www.sciencedirect.com/

- ScienceOpen.com https://scienceopen.com/

- PLOS.org https://www.plos.org/

- Microsoft Academic https://academic.microsoft.com/

- Mendeley https://www.mendeley.com/

For each article display on these websites, the extender requests a set of badges from the badger server. These are then inserted into the page’s HTML code after rendering the regular website as shown exemplary in the screenshot in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Badges integrated into Google Scholar search results (partial screenshot).

When the badger does not find information for a certain DOI, it returns a grey “not available” - badge instead. This is shown in the screenshot above for the outermost license and peer review badges.

The extender consists of a content script, similar to a userscript, adjusted to each target website. The content scripts insert badges at suitable positions in the view. A set of common functions defined in the Chrome extension for generating HTML, getting metadata based on DOIs, and inserting badges are used for the specific insertions. A good part of the extender code is used to extract the respetive DOIs from the information included in the page, which is a lot trickier than interacting with an API. Take a look at the source code on GitHub for details.

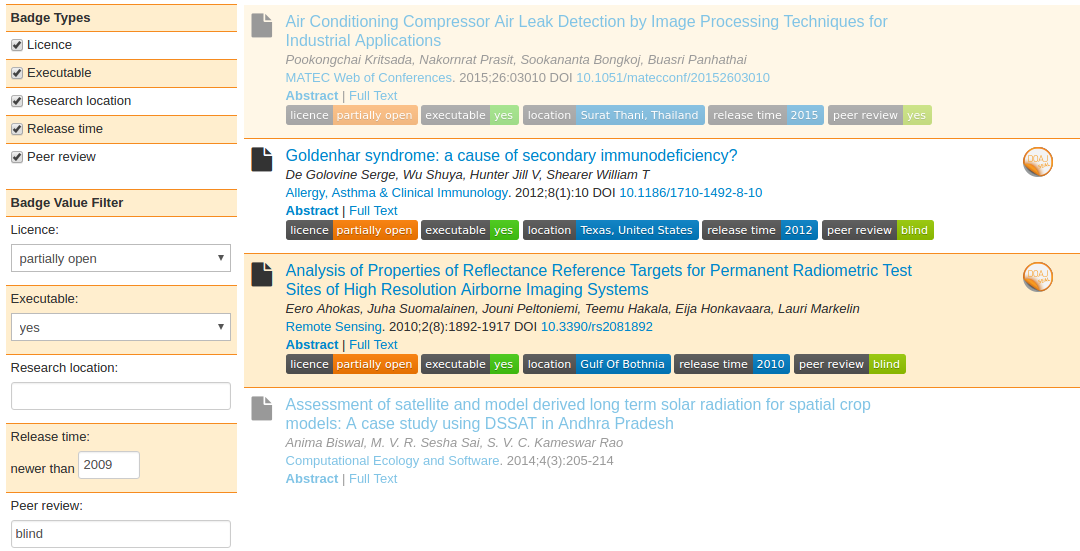

But the extender is not limited to inserting static information. The results of searches can also be filtered based on badge value and selected badge types can be turned on or off directly from the website with controls inserted into the pages’ navigation menus (see left hand side of Figure 8).

Figure 8: Filtering search results on DOAJ. Results not matching the filter or articles where the DOI could not be detected are greyed out.

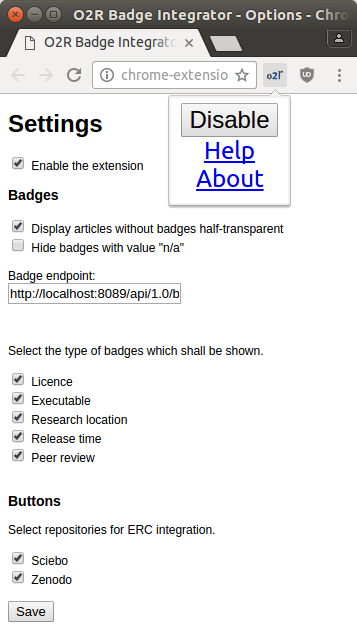

The extender is easily configurable: it can be enabled and disabled with a click on the icon in the browser toolbar. You can select the badge types to be displayed in the extension settings. Additionally it contains links to local info pages (“Help” and “About”, see Figure 9).

Figure 9: extender configuration.

Outlook: Action integrations

The extender also has a feature unrelated to badges. In the context of open science and reproducible research, the reproducibility service connects to other services in a larger context as described in the o2r architecture (see section Business context).

Two core connections are loading research workspaces from cloud storage and connecting to suitable data repositories for actual storage of ERCs. To facilitate these for users, the extender can also augment the user interfaces of the non-commercial cloud storage service Sciebo and the scientific data repository Zenodo with reproducibility service functionality.

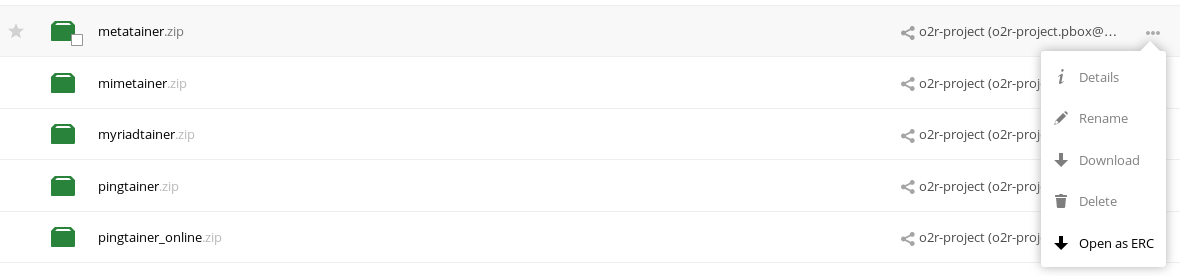

When using Sciebo, a button is added to a file’s or directory’s context menu. It allows direct interaction with the o2r platform to upload a new reproducible research paper (ERC) from the current file or directory as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Sciebo upload integration.

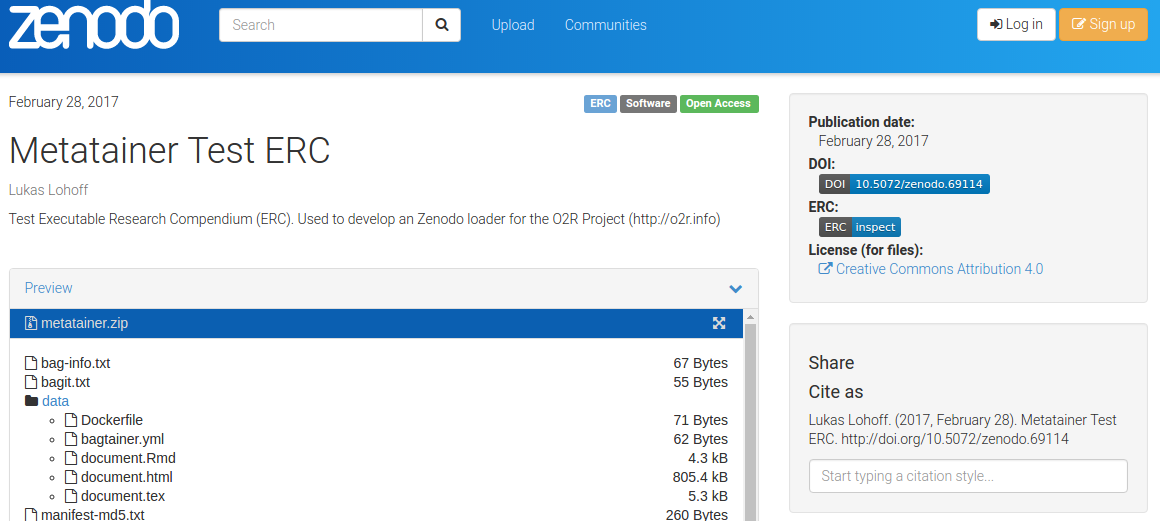

When you are viewing an Executable Research Compendium on Zenodo, a small badge links directly to the corresponding inspection view in the o2r platform (see Figure 11):

Figure 11: Link to inspection view and tag "ERC" on Zenodo.

Discussion

The study project Badges for computational geoscience containers initially implemented eight microservices responsible for six different badges types, badge scaling and testing. A microservice architecture using Docker containers was not chosen because of the need for immense scaling capabilities, but for another reason: developing independent microservices makes work organization much easier. This is especially true for a study project where students prefer different programming languages and have different skill sets.

However, for o2r the microservices were integrated into a single microservice for easier maintainability. This required refactoring, rewriting and bug fixing. Now, when a badge is requested, a promise chain is executed (see source code example). The chain reuses functions across all badges where possible, which were refactored from the study project code into small chunks to avoid callback hell.

A critical feature of extender is the detection of the DOI from the website’s markup. For some websites, such as DOAJ.org or ScienceOpen.com, this is not hard because they provide the DOI directly for each entry. When the DOI is not directly provided, the extender tries to retrieve the DOI from a request to CrossRef.org using the paper title (see source code for the DOI detection). This is not always successful or may find incorrect results.

The Chrome extension supports nine different websites. If there are changes to one of these, the extender has to be updated as well. For example, Sciebo (based on ownCloud) recently changed their URLs to include a “fileid” parameter which resulted in an error when parsing the current folder path.

As discussed above, in an ideal world the Chrome extension would not be necessary. While there are a few tricky parts with a workaround like this, it nevertheless allows o2r as a research project to easily demonstrate ideas and prototypes stretching beyond the project’s own code to even third party websites. Moreover, the combination of extender client and badger service is suitable for embedding a common science badge across multiple online platforms. It demonstrates a technical solution how the scientific community can create and maintain a cross-publisher, cross-provider solution for research badges. What it clearly lacks is a well-designed and transparent workflow for awarding and scrutinizing badges.

Future Work

One of the biggest source of issues for badger currently is the dependence on external services such as Crossref and DOAJ. While this cannot be directly resolved, it can be mitigated by requesting multiple alternative back-end services, which can provide the same information (e.g. DOAJ for example also offers licence information at least for publications), or even by caching. Furthermore, the newness of the o2r platform itself is another issue: licence, executable, and spatial badges are dependent on an existing ERC, which must be linked via DOI to a publication. If a research paper has not been made available as an ERC then a users will get a lot of “n/a” badges.

The extender is only available for Google Chrome and Chromium. But since Firefox is switching to WebExtensions and moving away from their old “add-ons” completely with Firefox 57, a port from a Chrome Extension to the open WebExtensions makes the extender available for more users. The port should be possible with a few changes due to only minor differences between the two types of extensions.

Other ideas for further development and next steps include:

- Interactive badges can provide additional information when hovering over them or when the badges are clicked, most importantly why and by who the badge was assigned.

- Provide the information behind the badges via an API.

- Create a common design for extended badges.

- Conduct a user study on extended and basic badges within a discovery scenario.

- Evaluating usage of badges in print applications and for visually impaired people (cf. COS badges)

For more see the GitHub issues pages of o2r-badger and o2r-extender. Any feedback and ideas are appreciated, either on the GitHub repositories or in this discussion thread in the Google Group Scientists for Reproducible Research. We thank the group members for pointing to some of the resources referenced in this post.

References

[1] Kidwell, Mallory C., et al. 2016. Badges to Acknowledge Open Practices: A Simple, Low-Cost, Effective Method for Increasing Transparency. PLOS Biology 14(5):e1002456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002456.

[2] Baker, Monya, 2016. Digital badges motivate scientists to share data. Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19907.

[3] Peng, Roger D. 2009. Reproducible research and Biostatistics. Biostatistics, Volume 10, Issue 3, Pages 405–408. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/kxp014.

[4] Peng, Roger D. 2011. Reproducible Research in Computational Science. Science 334 (6060): 1226–27. doi:10.1126/science.1213847.

[5] Lee, Duncan, Ferguson, Claire, and Mitchell, Richard. 2009. Air pollution and health in Scotland: a multicity study. Biostatistics, Volume 10, Issue 3, Pages 409–423, doi:10.1093/biostatistics/kxp010.

[6] Nüst, D., Konkol, M., Pebesma, E., Kray, C., Schutzeichel, M., Przibytzin, H., and Lorenz, J. Opening the Publication Process with Executable Research Compendia. D-Lib Magazine. 2017. doi:10.1045/january2017-nuest.